Considering Violence as History in Colombia

In my three weeks in Colombia, I’ve met many people who are quick to defend against the notion that the country is intractably violent. They point to the stereotypical nature of the claim, as well as the recent peace agreement between the government of President Juan Manuel Santos and the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia). Colombia is currently implementing the accord’s components, which include disarmament, rural development, amnesty for many former guerrillas, and the right to form a political party. On May 30th, the deadline passed for the FARC to turn in their weapons, with which the government plans to create a monument to the lengthy civil conflict.

In my three weeks in Colombia, I’ve met many people who are quick to defend against the notion that the country is intractably violent. They point to the stereotypical nature of the claim, as well as the recent peace agreement between the government of President Juan Manuel Santos and the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia). Colombia is currently implementing the accord’s components, which include disarmament, rural development, amnesty for many former guerrillas, and the right to form a political party. On May 30th, the deadline passed for the FARC to turn in their weapons, with which the government plans to create a monument to the lengthy civil conflict.

Yet, like many political undertakings, the process of peace is not so simple. In a hostel in Cali last week, I met a college student from Bogotá who had just returned from a research trip to a nearby FARC encampment now open to visitors. The weapons deadline is just an abstraction there, he told me, delayed by logistical issues. And though the area of Southwestern Colombia, once a stronghold of both the Cali cartel and, later, bands of FARC fighters, is safer now, with less likelihood of visitors to the jungle being hurt by guerrillas, government forces, or right-wing paramilitary fighters, visiting is still controversial. The student could not tell his parents why he had really come to this part of the country. With utmost discretion—literally under the table—he showed me a scarf he had purchased, on which were printed the faces of FARC leaders. While things today are safer and more accessible—commercialized, even—the meaning of the FARC is still highly contested. And coca growing and cocaine production in the region continue.

In place of evaluating the fact of Colombia’s history of violence, we might consider the subjective, political nature of deeming certain spaces and actors to be criminal. Controversies over the peace process point to a deeply historical phenomenon: the tendency to read non-state violence as illegitimate. I came here to investigate how Colombian policy began to operate with such meaning and, more specifically, what role the United States played in influencing notions and practices around public order. We must go back many years, well before the creation of the FARC in 1964, to understand the history of violence in Colombia as a set of ideas and, furthermore, as the result of practices of exclusion.

My research follows from the notion that early Cold War U.S. foreign aid, and its antecedents in the cultural and philanthropic spheres, operated at a nexus between economic development and security concerns. Starting in the late 1940s, United States actors saw Colombia as a laboratory to establish working models to achieve the anticommunist aims of international development. In so doing, they created deep connections between public order and the modernizing focus on human health and capitalist growth. I have begun to trace key moments in this narrative through a variety of Colombian archives.

Many of them are located in Bogotá, which has a large number of publicly accessible holdings with free research access and hours. At the Archivo de Bogotá, the IDPC (District Institute of Cultural Patrimony), and the Luis Ángel Arango Library, I looked at local government legislation, historical maps, rare urban planning texts, and local periodicals on microfilm. The documents tell the story of American involvement in urban planning projects in Bogotá, from the late 1940s efforts after massive riots destroyed large parts of downtown, to the early 1960s US Agency for International Development funding of a new neighborhood that would later be named Ciudad Kennedy, after the American president who laid its first brick. Bogotá’s Archivo General de la Nación (national archive) is a treasure trove of national government papers, even in the years of the dictatorship, including correspondence, legislative debates, reports, press records, and maps. It is the likely site of the bulk of future research.

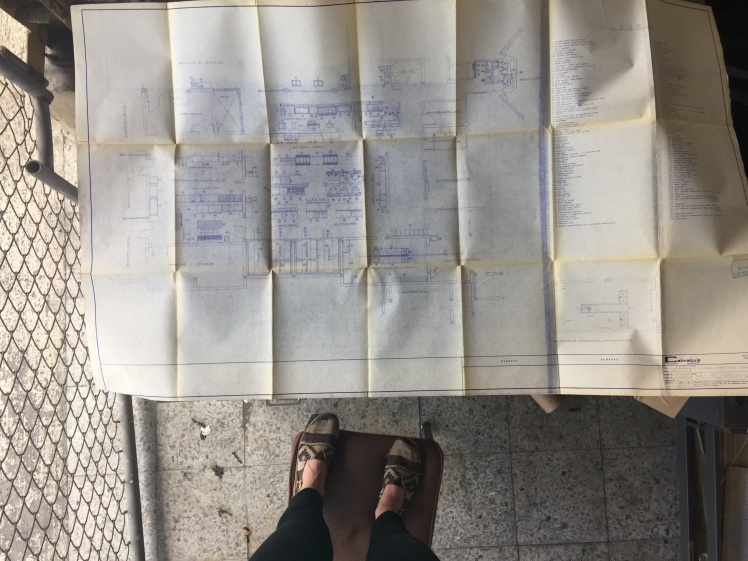

In the philanthropic sphere, the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations, both based in New York City, helped to create a model for US development aid abroad by work in Colombia, especially in agriculture. I examined documents related to their involvement at two universities in different cities: the Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá and the Universidad del Valle in Cali. Their administrative records, correspondence, and photograph collections evince the collaborative and extra-governmental nature of the funding, as well as the importance it placed on the physical plants of the universities themselves. Finally, I gained access to the CIAT (International Center for Tropical Agricultural Research) near the end of my visit, which the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations likewise contributed substantially to establishing in 1967. Located in Palmira, some kilometers outside of Cali in the Valle del Cauca, the institute reads like a Spanish hacienda made over for scientific inquiry. The staff gave me a full tour of the highly technical research laboratories, growing fields, and offices, as well as the sports, dining, and leisure facilities, all of which have remained mostly unchanged since the 60s. They introduced me to longstanding employees, furnished copies of construction photographs, and helped me pull dusty architectural plans out of an old file cabinet. Though it does not have an official archive, the CIAT represents the apex of my spatial research—not least for its proximity to that FARC encampment still out in the jungle. The history of the relationship between the two spaces, and between development and public order, remains important as the United States prepares to donate $450 million to the Colombian peace process.

Many thanks to the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies, as well as the College of Arts and Sciences, the School of Global and International Studies, the School of Education, and the School of Public and Environmental Affairs, for their generous support.

Amanda Waterhouse is a Ph.D. Student in the Department of History.